Photo credit vkara on 123RF

Much of FSG’s work with companies focuses on advancing various forms of equity (especially racial and gender equity) through philanthropic commitments directly to social justice movements or as part of their business practices and strategy in areas overlapping their corporate domains (e.g., financial inclusion, health equity, retail services). Across those engagements, there is one common place where companies (and many leaders) are getting tripped up (or entirely overlooking): the inner work of reflecting on their personal position and privilege when it comes to inequity.

In our experience, people that are leading meaningful (racial) equity work within companies invest in inner reflection. From the HR official leading an effort to increase representation of marginalized (e.g., BIPOC, women, LGBTQIA+) talent in the workplace to the CEO embarking on a DEI change management strategy, companies see the most progress when leaders invest significant time into their individual journeys on learning and un-learning. In our experience, those corporate leaders who aren’t setting aside the necessary time for this deeply personalized reflection often struggle the most with the pace of change and are in danger of snapping back to a status quo where the company fails to create an inclusive culture, tokenizes employees of color and other marginalized employees, and does not consider equity as part of its purpose.

What do we mean by inner work?

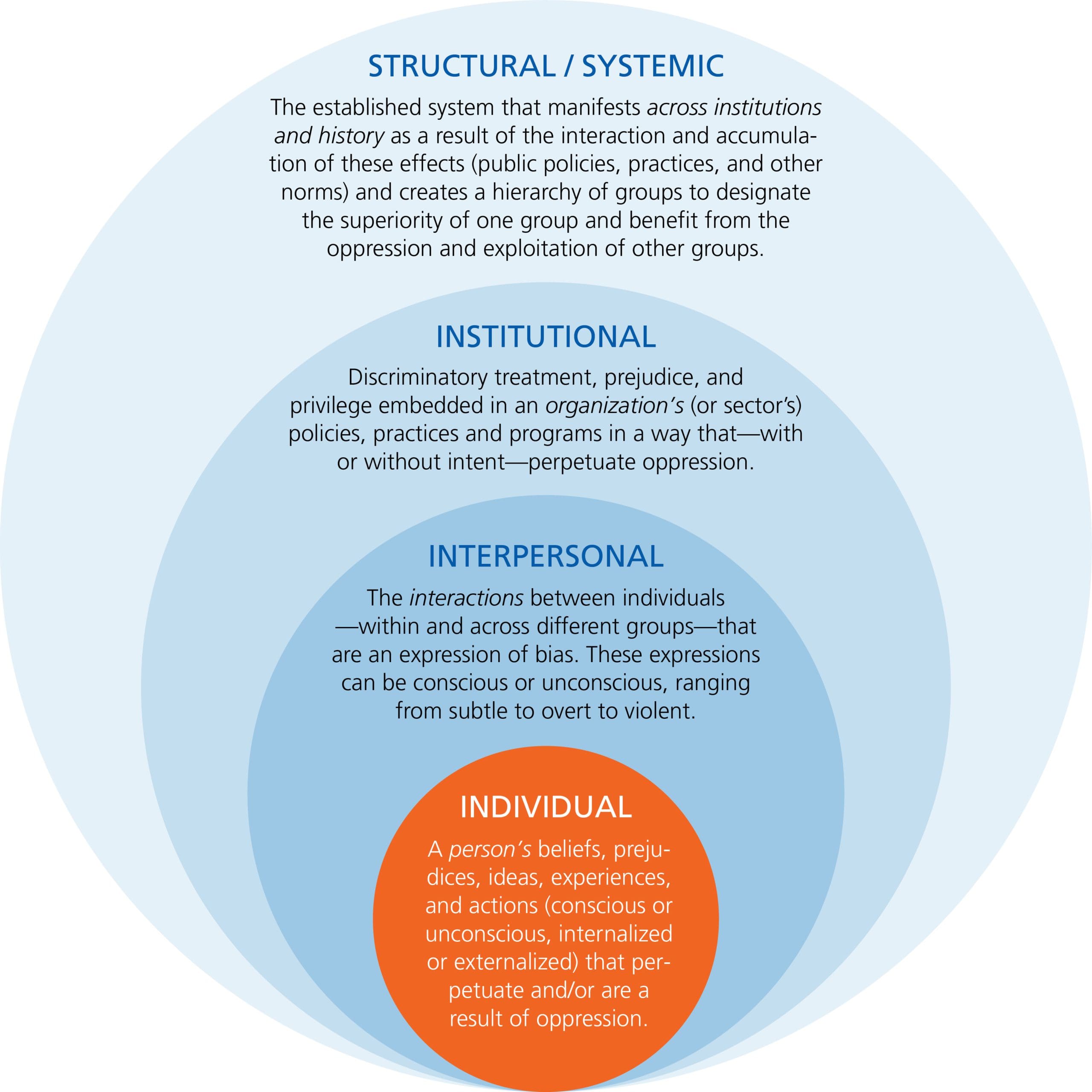

Equity work occurs at multiple levels. Many frameworks, such as National Equity Project’s Lens of Systemic Oppression or Change Elemental’s Systems Change & Deep Equity, describe four levels where oppression, such as racism, ableism, sexism, or homophobia, occurs and where the work to address it needs to occur: individual, interpersonal, institutional, and structural or systemic.

Inner work occurs at the individual level and can often make or break a company’s equity work, underpinning the ability to succeed at the other three levels. It involves a deep reflection on the ways in which people have personally benefited from, been harmed by, or perpetuated oppression. Inner work includes reckoning with one’s own internalized (and externalized) inferiority or superiority; with elements and experiences of individual, interpersonal, institutional, and structural harm; and with our conscious or unconscious complicity with forms of oppression.

Why is inner work important?

Equity work is layered but, without inner work, efforts remain shallow. We can’t change a system of oppression and inequity until we take the time to be in relation with the problem—to truly see yourself as part of the system—and to understand how it can both harm and benefit you. In the same way companies that want to work to advance racial equity can’t avoid looking their racist pasts (and present) in the eye, individuals and leaders who want to support and spearhead these efforts can’t avoid looking within and reckoning with their own histories with racialized harm. As a male leader, I cannot talk about equity without accepting and acknowledging that I have benefited from and perpetuated sexist and gendered norms in and outside of the workplace.

For example, we recently spoke to the CEO of a large retail company that made bold commitments to donate large sums of money to racial justice organizations and to advance racial equity within their company (e.g., increased representation in leadership ranks). The CEO shared frustration that he wasn’t seeing meaningful impact, that change wasn’t happening fast enough, and that he was still getting called out by his employees and local communities on inauthenticity. Until that point, the company’s equity efforts were primarily externally focused. But when the CEO starting doing his inner work, we saw the organization go from stagnant movement on internal equity efforts to hope and cooperation with employees of color. Through his inner work, which included a mix of self-reflection and learning independently and from employees, the CEO saw the problem differently, and he began to see himself in the problem. That, in turn, unlocked several opportunities and removed barriers that other leaders in the company were unconsciously putting up.

Inner work enables us to face our fear and reality on how oppression manifests within and around us. It means sitting with the uncomfortable truth that we all have biases and exhibit types of oppression, to interrogate accepted narratives about marginalized groups, to understand where we have become numb to groups’ struggles, and to accept the duality that (even despite best of intentions) an individual can simultaneously be part of the problem and part of the solution.

Inner work often starts by accepting and confronting our own biases. It means confronting and acknowledging the resistance, rationalization, fragility, and defensiveness within each of us that stems from our relative dominance or marginalization across a range of identities. Ultimately, it creates a deeper awareness of and value for others’ perspectives and ways of being. We are conditioned by the social, political, and economic norms around us to be numb to these observations, to shield us from having to recognize the impact of inequity and our participation in it. As we progress, inner work helps us increasingly accept these realities without fear and use the energy that comes from that acceptance to help heal and find healthy ways to find solutions.[1]

I can sympathize with the retail company CEO who is frustrated with the pace of change and having a hard time doing his inner work. As a brown-skinned South Asian man and the first-generation son of immigrants to the US, I’d always encountered a tinge—and often a swath—of racism in a post-colonial world. People would (and still do) make assumptions about my background; classmates, teachers, and neighbors regularly tried to convert and ‘save’ me; and micro-aggressions and being undercut at work became synonymous with my daily experience. But that tinge became much more acute in a post 9/11 world where I regularly began to be profiled as a potential terrorist.

In the midst of processing my anger and trying to understand what was happening to me and my country (the United States of America), I had the epiphany that I and my community were not immune to holding deep-seated prejudices. There is rampant colorism, anti-Black racism, sexism and misogyny, and homophobia (to name a few) in the South Asian community, not to mention the anti-Muslim rhetoric I regularly heard from Hindu and Jain community members at the dinner parties that were a near weekly occurrence of my childhood.

As I did my own inner work, I had to recognize that, at times, I have benefited from some forms of oppression (e.g., sexism). I have shared about my own journey and these complex feelings with clients when talking about equity and the importance of inner work. As a brown-skinned male with considerable positional power, I feel shame about the times when I am able (and have had) to assimilate and stay silent to advance or succeed while others cannot. On the flip side, there have been times when the cost of silence felt too high and overtook the fear of retaliation or being fired (whether by a client or my employer). Confronting those dualities—and that both are part of my identity, both when I have and have not used my power to either maintain status quo and inequities or to create change—is part of my inner work.

On a near daily basis, I still wrestle with wondering when to speak up (or not). When I do speak up, I often second-guess myself. Was I too diplomatic in my approach when I spoke about inequity? Was I too strident? And I am always aware of my feelings of envy towards my white friends, classmates, and colleagues who are free from dealing with the everyday pain of experiencing racism in the ways every action you take is judged, every movement is evaluated, every word you type is hyper-analyzed. Feelings of envy that their lives seem less chaotic because they don’t have to think about the spaces you can or cannot move within the world, where you are welcome or not, what positions you will or won’t be considered for in the workplace, and what opportunities you will have access to or not.

In conversations with clients, we talk about how these conflicting feelings are part of the journey and that its okay to have them. The important part is to push through—not to hold back or think these feelings disqualify you from doing equity work—and that modeling vulnerability with their teams and other leaders can be a powerful mechanism for change in the company. We also talk about how my journey is not over; inner work is never done. It is ongoing because equity work is a practice/behavior and not a fixed state of being reached through a prescribed set of steps. My inner work continues as I unlearn a lifetime of structural, systemic conditioning and learn from others’ experiences. That inner work journey will continue even as I support organizational change to advance equity at FSG and for our clients. It also means an increased willingness to be vulnerable, to share my journey and insights, and to bring these deeply personal experiences into my professional coaching and advising to create social change.

I remember I was petrified the first time I shared about my inner work and journey with a client. How would it be received? Would they think they made a mistake hiring us to do the work? Overwhelmingly, folks have told me how validating and helpful it is to hear, and how it gives them the assurance and license to share their own struggles, their journey and to make mistakes but to learn from them along the way.

How does the inner work change equity efforts?

Everyone’s inner work leads to different learnings, introspections, and implications for how those manifest in the work. In both my personal experience and observations of others (clients, colleagues, equity leaders), here are some of those outcomes from the inner work:

- Taking a more authentic, humble approach to learning; a recognition of the need to inform the work with multiple perspectives and an acknowledgement that multiple, seemingly conflicting views can be true at the same time

- Increased willingness to engage in deep historical analysis of systemic oppression (e.g., structural racism and racialized power analysis), applied to the self as well as the organizations, institutions, and systems they seek to impact

- Reduction of the “competitive” mindset and reputation-guided actions; recognition that to truly advance equity will require multiple/all—including “competitors” in the industry—to work together

- Desire to deepen proximity and exposure to diverse, non-dominant perspectives in non-transactional, non-exploitative ways; a recognition that filling out a board or C-suite with missing diverse talent, or increasing community partnerships and voice in business processes, is not a “dilution” or “check the box” exercise, but will help create impact and improve the business—e., a greater recognition of the moral and business imperative for equity; not a zero-sum game; we all benefit from equity

- Increase in compassion (radical kindness) in the equity work and beyond; deepening of the capacity to skillfully and effectively engage these individuals and organizations in non-tokenizing, non-exploitative, and non-superficial ways that avoid shame and erasure, bring people in to advance the collective work, improve relationships and, ultimately, lead to better business outcomes

If companies want to do the work of equity, they have to start with the individual work.

What often stops people from doing inner work is the fear of being a bad person or being found out. Equity work—and, therefore, inner work—is not about being good or bad, but doing what is needed. Changing a system does not happen through a series of superficial efforts to paint over the harm of the status quo; it requires deep change within a critical mass of powerful actors who are helping to maintain the system, sometimes unintentionally.

“The success of the intervention is based on the interior condition of the intervener.”

– Bill O’Brien

Do the inner work because otherwise the broader equity work at an organization or systemic level remains academic or a boardroom exercise, an outsider’s view of what is needed that lacks the realities of lived experience—whether you have suffered from marginalization and oppression or not—to result in meaningful change at the interpersonal, institutional, or systemic levels.

[1] “Systems Change & Deep Equity: Pathways Toward Sustainable Impact, Beyond “Eureka!,” Unawareness & Unwitting Harm.” Change Elemental. Sheryl Petty and Mark Leach.