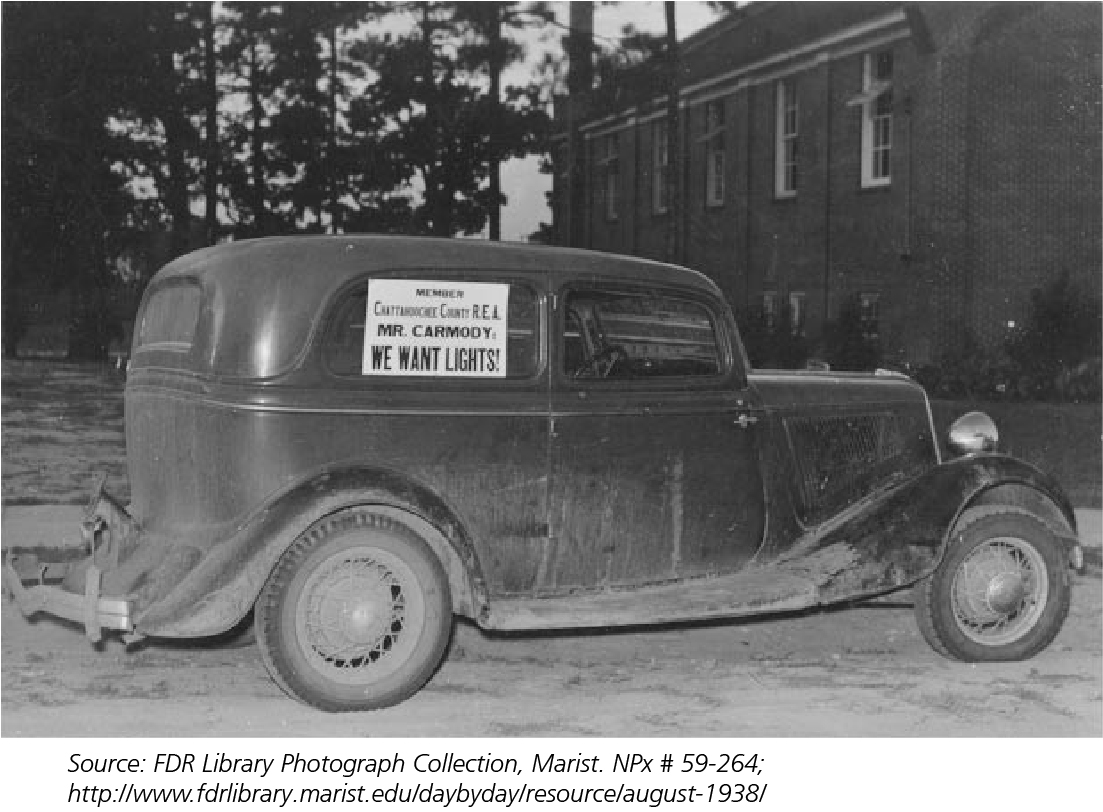

“Mr. Carmody: We Want Lights!” This sign greeted John Carmody, head of the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) in 1938 as he was visiting residents in Georgia to hear their opinion of public rural electrification projects. Five years before, the nearby Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was established as a major project of the New Deal to build dams along the rivers of the Tennessee Valley to improve their navigability, produce fertilizer and support agricultural education for farmers, and most importantly, to provide affordable electricity to local communities. As a result of the project, people living in rural communities were able to use new farm equipment, appliances like refrigerators and radios, and electric lights. President Roosevelt created the REA in 1936 based on the success of the TVA to fill the gap left by private electricity companies who deemed it too expensive to connect and supply rural homes. As John Carmody heard in his tours, rural communities were eager for affordable electricity, despite the reluctance of private companies to serve them, even with the availability of low cost federal loans. Through close partnership with communities, the REA helped create over 400 electrical co-operatives that served 288,000 households and brought the rural electrification rate from 10% to 25% by the end of the 1930s.1

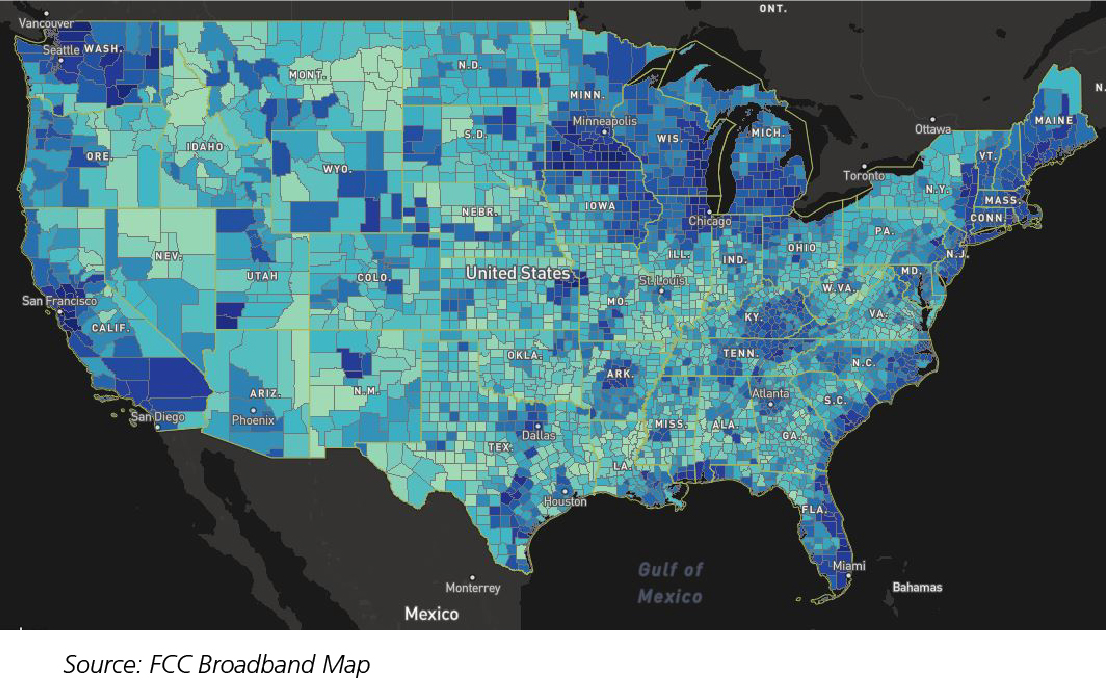

As in the 1930s, rural communities today face disparate access to a crucial technological link to modern society: broadband internet. To be clear, the “digital divide” affects people living in both rural and urban communities, with many families unable to pay for internet service or digital devices, but access problems are particularly pronounced in rural areas where broadband service is often unavailable or too slow, and public resources like libraries are less accessible. A 2018 FCC report found that only 69% of Americans have access to fixed broadband service 25Mbps or faster, compared with 98% in urban areas.2 Access is particularly limited in the rural south and west; in Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, Oklahoma, California, Alaska, Missouri, and Mississippi, fewer than 50% of rural residents have access to fixed broadband service. Unsurprisingly, there is a correlation between access to broadband and internet use: 92% of urbanites use the internet and 83% own a smartphone, whereas only 78% of rural residents use the internet and 65% own smartphones.3

The implications of this disparity are wide reaching. Over the past 20–30 years, use of the internet has reshaped every aspect of modern American life, and change continues apace as developments like artificial intelligence and the internet of things further our economy and society’s connectedness to the internet. Rural communities without access to broadband are not only cut off from these broad developments, they are also cut off from services that are uniquely suited to improving rural economies and quality of life. Particularly notable are the opportunities that broadband provides in the areas of economic development, education, and health:

- Economic Development: Access to broadband provides rural communities with a host of economic opportunities, including the opportunity for products and services to reach new markets, for businesses and families to access different kinds of financial services, for community members to work remotely from their rural homes, and for industries like farming to make use of the latest technology that can save costs and increase productivity.

- Education: Similarly, broadband provides rural communities with access to educational resources that can help local students and professionals learn crucial digital and technical skills. Additionally, broadband enables communities to access a much broader range of educational resources than what might be available otherwise. This includes both complete educational systems like Summit Learning that provide schools with the tools to enable “personalized learning,” free on demand resources like Khan Academy or Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) that allow for the independent pursuit of learning, or online universities that provide post-secondary education credentials.

- Health: Rural communities often face unique health challenges, including high rates of chronic disease and a disproportionate impact from the opioid crisis. These challenges are amplified by a shortage of healthcare providers. Broadband access can enable services like telemedicine and remote patient monitoring that allow rural patients easy access to high quality care. For example, Project Echo is a program of the University of New Mexico that pairs expert specialists in academic medical centers with rural primary care providers to train and coach them in treating patients with complex conditions.

Increased broadband access on its own will not be enough to solve for the disparities in income, health, and education that rural communities face. Nevertheless, broadband is a vital tool that can connect rural communities to a multitude of opportunities and resources that otherwise would not be available to them.

There are many challenges and opportunities associated with expanding rural access to broadband. At a fundamental level, the economic incentives are not strong enough for private internet service providers to prioritize costly network expansion in rural areas. And even when communities do have broadband access, there are often significant start-up costs associated with implementing broadband enabled services like telemedicine and digital learning tools for schools. What’s more, the data on the geography of broadband access is variable in quality, making it difficult to get a full and accurate picture of the challenge and to make detailed decisions about where to prioritize investment. The federal government is playing a primary role in helping to address these challenges through programs such as direct investment in broadband expansion through the FCC’s Connect America Fund, which in 2018 used a reverse auction to commit $1.5B in investment over 10 years to provide broadband to over 700,000 locations in 45 states. The Department of Agriculture also operates programs investing over $700M annually in expanding rural broadband access, including grants and loan guarantees for projects that extend networks or support implementation of telemedicine and education programs.

Corporate and private foundations are also playing a role in helping expand rural access to broadband. On the corporate side, Microsoft’s Airband Initiative is pairing the deployment of technology that uses whitespace in the TV spectrum for broadband with philanthropic partnerships to teach digital skills. On the private foundation side, in Minnesota the Blandin Foundation invests in building the capacity of rural communities to research and plan for broadband expansion. An evaluation of broadband expansion in five rural communities supported by the Blandin Foundation found that the communities saw fast return on their investment and improvements in healthcare, school systems, and local economies. While these initiatives are promising, there is significant opportunity to further support rural communities in helping them to plan and access broadband, as well as for continuing advocacy to close the rural digital divide.

One final note of consideration as we think about expanding broadband access. Any expansion of broadband must consider the extent to which and whether there are variations in who experiences the benefits, and whether the burden of new infrastructure falls disproportionally on particular groups of people. An important lesson from the TVA’s expansion of electricity is that the dams built as infrastructure to generate power flooded many areas. This flooding disproportionately displaced many black sharecroppers who didn’t own the land and were thus out of work, not compensated, and excluded from land grant colleges and programs.4 Another critique of the TVA is that it did not stem migration to urban areas. Similarly, broadband access in rural areas may not slow migration to cities today, but improving quality of life and access to economic opportunity for rural communities are worthwhile goals in and of themselves.

And so, while we have successfully electrified rural America, technological access gaps in rural communities persist and contribute to many of the same challenges rural communities faced in the 1930s. Rural communities are hungry for broadband: a 2018 Pew Research poll found that 58% of rural Americans believe access to high speed internet is a problem in their area, with older and nonwhite respondents seeing access as a major problem.5 A modern day John Carmody touring rural communities would be pleased to find them electrified, but might be likely to see a familiar sign: “Mr. Carmody: We Want Bytes!”

References:

-

"Mr. Carmody, We Want Lights:" The Tennessee Valley Authority and Rural Electrification Under the New Deal. Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Encyclopedia.com. 15 Feb. 2019 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>.

-

“2018 Broadband Deployment Report,” Federal Communications Commission, 2 Feb. 2018.

-

"For 24% of Rural Americans, High-speed Internet Is a Major Problem," Pew Research Center, 10 Sep. 2018.

-

"Mr. Carmody, We Want Lights:" The Tennessee Valley Authority and Rural Electrification Under the New Deal. Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Encyclopedia.com. 15 Feb. 2019 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>.

-

Ibid.