Building Empathetic Agility: The Leadership Muscle for Navigating Complexity with Purpose

Empathetic agility is the ability to adapt strategically and maintain momentum, while genuinely considering the experiences of others.

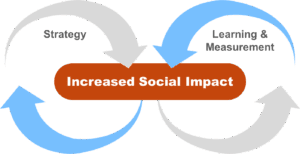

As social impact consultants, we believe the real purpose of evaluation is not just to report metrics, but to guide better decisions that create greater impact. Too often, evaluations focus on narrow metrics to demonstrate accountability but miss the bigger picture.  Programs operate in complex, shifting contexts, and without understanding the deeper factors shaping outcomes, decision-makers may misjudge what works and why.

Programs operate in complex, shifting contexts, and without understanding the deeper factors shaping outcomes, decision-makers may misjudge what works and why.

A new approach: Evaluations, whether formative (early/during implementation) or summative, should be learning-oriented—helping funders and implementers adapt, avoid wasted effort, and strengthen real impact.

Take FSG’s PIPE program as an example, which aimed to improve early years learning outcomes by replacing rote learning with activity-based learning (ABL) through interventions such as developing curriculum and lesson plans, introducing learning aids, and training teachers, among others.

What traditional metrics may have missed: Evaluation during implementation discovered that many teachers recognized ABL’s value, but hesitated to adopt it for fear of being reprimanded by school owners, who themselves catered to parents preferring rote learning.

Without identifying this barrier, metrics alone could have painted an incomplete—or even misleading—picture of accountability and impact. Insights like this show why evaluation must go beyond counting activities and reach to uncover what truly drives or hinders change.

Learning-oriented evaluation applies to all types of programs, big or small, charitable or systemic. Barriers such as limited resources or focus on inputs shouldn’t deter us—because the heart of evaluation is about asking the right questions, to the right people, in the right way. Methods can always be adapted in scope and scale.

Unbounded learning can yield many insights, but its value is diminished if decision-makers are unclear about which actions can improve strategy. Instead, scope your inquiry so it directly links to validating or iterating the program’s strategy or theory of change. Key questions might include:

Match the questions to the program phase: The right questions are also a function of the phase or evolution of a program, which will define the terms ‘issues’ and ‘impact’ in the above questions. Since outcomes could take years to emerge, identify and assess intermediate markers along the pathway to change in formative evaluation.

Example: In the post-pilot phase of iDE Cambodia’s market-based sanitation program, active marketing and sales by small toilet businesses, and profitability served as intermediate outcomes toward the end goal of increased toilet adoption and universal basic sanitation. Ongoing evaluation confirmed profits but flagged weak promotion efforts and identified why owners engaged less than expected, which prompted a pivot to a managed salesforce model.

Make root cause identification an explicit part of every evaluation: Don’t stop at surface-level questions; dig deeper to understand why interventions are (or aren’t) working, and what the characteristics of an effective partner are. While root cause analysis, delving into relationships, connections, and mental models, is often associated with systems change, it is a universally applicable principle—simply asking “why?” can help identify the critical issues and/or the actors whose involvement could yield outsized impacts. Example: India’s well-known mid-day school meal scheme was developed after identifying food insecurity as a primary root cause of low enrolment and attendance. The intervention simultaneously addressed nutrition and unlocked the value of other educational investments (e.g., infrastructure, teacher training, curriculum development).

Focus evaluation on contribution, not attribution: While attribution (isolating a program’s unique impact) can be appealing, conclusions would likely have limitations because most programs operate in complex systems alongside other programs, actors, and contextual factors. For instance, to what extent are learning outcomes attributed to one program’s school infrastructure improvements compared to another program’s curriculum and teacher training interventions? By contrast, contribution analysis helps illuminate your program’s unique value within the broader ecosystem, informing choices about activities and partnerships that will maximize impact, ROI, and communication with stakeholders. Continuing the example, show contribution through plausibility: learning aids complemented curriculum and teacher training, and together they improved learning outcomes. The emphasis is on each intervention being necessary, but insufficient, and on the plausibility of contribution towards outcomes, subject to an intervention being valued by stakeholders.

Actor mapping is indispensable. A superficial mapping of immediate stakeholders is unlikely to reveal root causes or identify leverage points. It could also miss actors who do not have a ‘stake’ in the outcomes (thus, not ‘stakeholders’) but may wield influence over an initiative or be influenced by it. The goal is not to capture every actor, but to identify and illuminate:

Participatory approaches are fundamental to learning ground realities and refining strategy. They go beyond interviewing end users or beneficiaries to learning from other key actors and their contexts.

There is no perfect evaluation design, but progress starts small. What matters is building a culture of learning—staying curious, open, and adaptive. By treating evaluation as a journey of discovery rather than compliance, funders and implementers can strengthen strategies, unlock hidden barriers, and ultimately drive greater impact.

Empathetic agility is the ability to adapt strategically and maintain momentum, while genuinely considering the experiences of others.

What does 2026 mean for the future of social impact?

Achieving impact through AI will require purpose, intentional deployment, and responsible risk management.

You will also receive email updates on new ideas and resources from FSG.

"*" indicates required fields

You will also receive email updates on new ideas and resources from FSG.

"*" indicates required fields

Get updates on new ideas and resources from FSG.

"*" indicates required fields

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |