Turn on the news today and you’ll see political, academic and corporate leaders alike, all clamoring to find a remedy for our ailing global economy that everyone can agree on. The cacophony is deafening, and there is no shortage of solutions being presented. Debates aside, the current global economic predicament has forced virtually everyone in the U.S. to make tougher decisions on the allocation of resources.

Funding for the global HIV/AIDS program has not been immune to these tightening U.S. budget restrictions. Thirty years after the first HIV diagnosis and almost a decade into the PEPFAR program, the monumental push for a response to the epidemic has down-shifted. The proposed 2012 U.S. global budget for HIV stands at $5.6 billion, virtually unchanged from 2011’s budget and only marginally greater than 2009 spending of $5.5 billion two years ago. These static numbers underscore what has been called the "flat-lining" of the U.S. commitment to HIV. It is mirrored by a shifting global agenda in the push for greater alignment of HIV with other initiatives, including non-communicable disease interventions (as discussed in detail in the recent post, NC-What?) and health-system strengthening strategies.

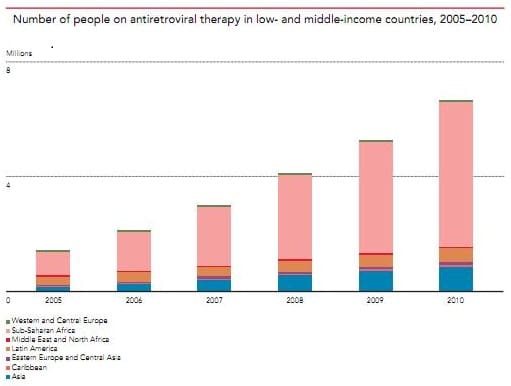

These new changes come on the heels of the treatment as prevention findings and stand as a major roadblock in the push for increased treatment coverage. According to UNAIDS’ "Aids at 30" report, with 1.4 million new patients starting treatment in 2010 and the global incidence rate dropping 25% over the same year, the results continue to support treatment as an effective strategy in transmission reduction. Yet without continued funding growth to match the rising demand for expansion of treatment, the progress against HIV is in jeopardy of stalling.

As HIV passes its 30th birthday, what does the flat-line in funding mean for future growth in treatment? The international community’s ambitious goal of reaching 15 million HIV+ people on antiretroviral therapy by 2015 means adding ~10 million patients to ART over the next few years. Considering that there are currently 6.6 million people on treatment today (according to the Aids at 30 Report), that means the number of patients on ART would have to grow ~32% each year for the next 3 years. By contrast, the whopping 1.4 million patients who were added to treatment in 2010—a substantial increase—amounts to 27% growth over the prior year. For this level of growth to continue (let alone increase further), it will require significant increases in funding for care and treatment programming over the long term.

The real challenge of supporting such growth lies in the snowballing cost of maintaining existing patients on treatment—the so called “treatment mortgage”. For each additional patient who goes on treatment, donors have taken on another lifetime commitment of paying for ART. Current estimates of the average cost of antiretroviral therapy (ART) can vary and nailing down a number is difficult. However, for the purposes of this blog, a quick read reveals that estimates generally range from $100 to $850 per patient per year. Splitting the difference and assuming an average cost of $500 for treatment worldwide, if we then apply that cost to the 6.6 million HIV+ individuals currently on treatment worldwide, the ongoing annual core cost of keeping those patients on ART is ~$3.3 billion, or roughly half of the current 2012 budget. Multiply that by the number of years each patient will be on treatment (say 20) and the total cost of treatment rises to about $66 billion—just to maintain current patient levels.

The prospect of adding roughly 3 million additional people on treatment a year for each of the next 3 years translates to $1.5 billion per year in added treatment costs. Therefore, in order to match the rise in costs of treatment (not including the indirect costs of diagnostic tools, commodities, health personnel, etc.), the budget would have to increase 27% next year alone.

A further factor of consideration for the “treatment mortgage” is the impact of increasing levels of resistance on treatment selection and the rising cost of new medicines. Treatment failure due to resistance is a major phenomenon in resource-poor places like Sub-Saharan Africa, the scale of which is only starting to be fully understood. As more resistance to first-line regimens is diagnosed, the demand for new and more expensive treatment regimens will likely rise with it and potentially cause further strain to the global treatment budget. MSF reports that the impact of changing a patient to newer second line therapy can increases costs per patient by as much as 6 times (MSF July, 2011 report). That multiple rises to almost 20 for third-line treatments ($2,766 per patient per year versus and average of $143 for first-line ART). If price reductions don’t occur in step with shifting demand for these expensive second and third-line drugs, these price increases could cause average treatment costs to balloon.

One potential relief to the treatment mortgage dilemma comes in the benefits of prevention. According to a recent article summarizing WHO impact projections, the expansion of the global HIV program could avert as many as 12.2 million in new infections and 7 million deaths between 2011 and 2020. These numbers are based on the WHO's new targeted recommendations for programming that assume only 13.1 million patients on treatment by 2015. From a funding perspective, that translates into $6.1 billion in savings on patient treatment per year (assuming our $500 average cost of ART per patient per year), or $122 billion if we again assume a lifetime treatment commitment of 20 years per patient. Therefore, by increasing cost outlays in the short term to improve the number of HIV+ patients on treatment, the international community could potentially improve the longer term sustainability of funding for the HIV mortgage by significantly reducing the growth of the mortgage. And while the true impact of these cost savings is difficult to project, the social impact of the lives saved through increased access to treatment is immeasurable.

In order to sustain the progress against HIV, the U.S., as a leader in the fight against HIV, will need to reexamine the long term implications of its flat-lining budget commitments. Taken together, the anticipated costs in treatment of sustaining the current progress against HIV undoubtedly present difficult tradeoffs for stakeholders and program administrators alike. But the potential human benefits of achieving scale in HIV treatment are beyond question. Policymakers must look at the future of HIV funding in light of all of these perspectives—not just the immediate.