What do you get when you combine a quarter cup of water with table salt and a zap from a car battery? Enough chlorine to purify 200 liters of drinking water.

I was fascinated last spring when I first encountered the MSR SE200 Community Chlorine Maker at the annual PATH Community Breakfast innovation fair—fascinated not only by how something so small could pack such a punch, but also by the story of how an outdoor recreation equipment company came to partner with one of the world’s leading global development nonprofits around water purification.

I recently had an opportunity to learn more about the project when Patrick Diller from MSR (Mountain Safety Research) Global Health and Jesse Schubert from PATH joined me in a community conversation about innovative corporate-nonprofit partnerships.

Interestingly, I learned that the Chlorine Maker originated from a 1999 MSR-DARPA partnership, which yielded a pen-sized device that provided troops with the ability to create enough chlorine to purify up to 4 liters of water in 30 seconds. MSR quickly realized that many of their products had the potential for broader global health applications, and wanted to think about how to leverage their technology for global good.

They started by donating these water treatment devices to Southeast Asia tsunami victims. What they learned in their subsequent journey fundamentally shaped how they approached social investments and led to the creation of a new, for-profit business division, MSR Global Health.

What they learned:

- The chlorine maker, as originally conceived, was incompatible with meeting the communities’ water needs. As MSR reflected on their website: “Though well-intended, this philanthropic effort was also humbling in several ways. Complicated logistics hindered our ability to get the products into the disaster zones quickly. And once in, our small devices—perfect for backcountry users—were impractical amid such enormous demand for clean water that entire families could depend on.”

- While MSR had a great deal of technical expertise, they had little experience with marketing to low-income consumers and operating in resource-constrained environments. They needed partners who brought different skillsets, relationships, and lived experiences.

- In the interest of making these investments self-sustaining, MSR was thinking about this new venture as a business line, not a philanthropic donation, yet had limited capital to invest in product innovation and market research. They needed investment.

What they did:

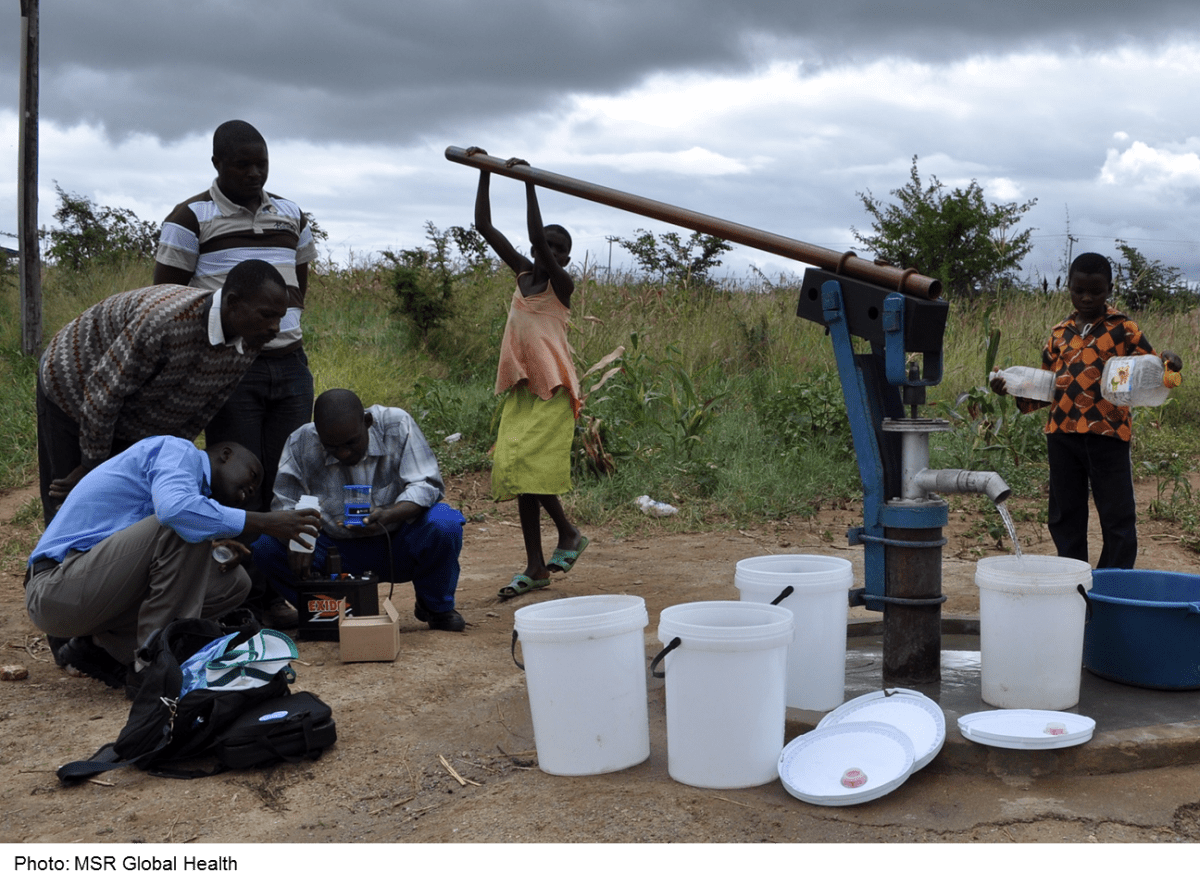

- Found strong partners: MSR recognized that they needed partners who shared their vision for clean water, brought complementary knowledge and skills to the project, and could provide perspectives on how MSR could best make a difference in global health. PATH brought market knowledge and innovative approaches for increasing access to appropriate water treatment products among low-income communities. World Vision, one of the leading NGO providers of clean water, brought a trusted presence in many affected communities around the world, used their “boots on the ground” to identify the best places for field trials, and worked with local community leaders to gather timely feedback to inform the next chlorine maker prototype.

- Attracted foundation dollars to catalyze corporate research and development: MSR and PATH quickly found several foundations that shared their desire to deliver clean drinking water, and who were willing to subsidize the product development process. With investments from foundations like the Laird Norton Family Foundation and the Lemelson Foundation, MSR and PATH co-designed the prototypes for the core technology—including a much simpler design requiring locally-available inputs.

- Developed trusted relationships and recognized limitations: Every transformational partnership is based on a foundation of trust. For MSR, PATH, and World Vision, it began with articulating a shared understanding of what they individually and collectively were trying to achieve—making implicit motivations explicit. It also involved a commitment to co-creating the strategy and recognizing which core competencies they each brought to the partnership. Finally, the partnership required patience—understanding that nonprofits and corporations can work on different timetables, which could either slow down or speed up the process.

Where’s the partnership now?

In May of 2015, MSR launched the MSR Global Health division—it has a separate brand, webpage and distribution network, as well as an objective of turning a responsible profit. According to a recent New York Times article, 20 percent of the MSR research and development budget is now going to global health-related products. PATH and MSR Global Health are continuing to innovate together and are currently working on a chlorine maker that can create chlorine around the clock, which is critical in settings such as refugee camps.

Many thanks to Jesse Schubert, Technical Officer at PATH and Patrick Diller, Marketing Manager at MSR Global Health for joining me in the community conversation, and to Lawrence Fuell at Shoreline Community College for hosting the event. To learn more, watch our full conversation.